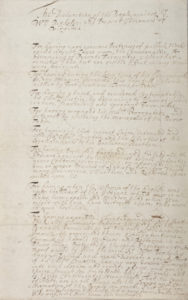

“Gentlemen and Fellow Soldiers, How am I transported with gladnesse to find you thus unanimous, Bold and daring, brave and Gallant; you have the victory before you fight, the conquest before battle. I know you can and dare fight, while they will lye in their Place of Refuge and dare not soe much as appeare in the Field before you: your hardynesse shall invite all the country along as wee march to come in and second you.” (Jameson p.129)

After a long series of exchanges and conflicts of interest with his governor, Nathaniel had followed his trail of passion and drastic action to its extreme. After opposing Governor Berkeley and acting against his will, Bacon was now going to remove the seat of government. He thus ordered his men to siege and burn Jamestown, the largest city in Virginia’s colonial territories.

What would drive a young, idealistic son of the English aristocracy to such rebellion, such violence and aggression? Why would a planter take up arms and lead a a rabble of men across his colony, killing natives and pillaging the homes of those who opposed him? Nathanial Bacon’s dynamic past and colorful character was sparked by the conflict in opinion he had with his old family friend and distant cousin, Governer William Berkeley, Virginia’s highest colonial authority. To understand Bacon’s actions, you must understand his relationship with Berkeley and the events that unfolded as a result of confrontation with Virginia’s native population and misunderstanding between the two spirited gentlemen. The events that unfolded would change the course of Virginia’s colonial history until the American revolution, almost exactly one hundred years later.

Nathanial Bacon was a young man with a thick and rich past. He grew up under the care of his father, a Suffolk gentleman by the name of Thomas Bacon. The younger Bacon attended school as a young man and recievd his higher education at Cambridge University. There, he gained a reputation amongst his peers and professors as a young man who “could not contain himself within bounds” even though he was privy to a “genteel competency.” As one of his mentors John Ray wrote, he had “very good parts and quick wit” but was “impatient of labor, and indeed his temper will not long study.” His temper and reputation were his downfall there, and during his third year of school, he was withdrawn by his father from Cambridge, specifically for having “Broken into some extravagencies.” (Washburn, p.18). As Bacon grew into adulthood, his reputation grew with him. In his early twenties, he fell in love with the daughter of Sir Edmund Duke of Benhall, Elizabeth Duke, and they were soon after married. Upon receiving the news of the marriage, her father disowned her and never spoke to her again. This action sharply demonstrated both Duke’s love for Bacon, and her father’s disdain of him. As if all of this weren’t enough evidence of the young man’s character, Bacon soon after was caught attempting to wedge his was into another’s inheritance, at which point Bacon’s father felt forced to draw a line. More so for the sake of his own reputation than for the welfare of his son, Thomas Bacon arranged for Nathanial a trip to the new world, allocating him both passage and £1,800 with which to start a new life away from his poorly established reputation. To ease his father’s worries, Bacon would set sail for Virginia where his cousin and friend, William Berkeley was governor (Morgan, p. 254).

William Berkeley was a ripe old man of seventy in 1675 when Bacon, only twenty nine, arrived with his wife. He had fought viciously for years against the Native Virginian population, defeating Opechancanough and forcing the tribes of Virginia’s former Powhatan Confederation into peaceful submission. He had supported the Cavaliers during the English civil war, and apart from a short period during Cromwell’s reign, had been ruling Virginia for the better part of his life. So loved was he by the people of Virginia that their outcries were numerous enough for Berkeley to be instated against the better judgment of the king, who did not want to upset the colonials so far from the reach of his direct authority across the Atlantic. Thus at the time of Bacon’s arrival to the colony, Berkeley had been recently reappointed as royal governor to save the king the risk of insurrection despite his age. As a personal favor to Bacon, Berkeley helped him establish a plantation north of Jamestown at what is now Curls Neck and gave him a seat on the governing council of Virginia (Morgan, pp. 254, 255). It would not be long however before Bacon, who seemingly demonstrated no desire to establish a good name for himself among the Royalists, would demonstrate his defiance and uphold his reputation for rash behavior and a lack of respect for authority.

The conflict as remembered by Thomas Mathew, began with three major events, “three Prodigies in that Country, which, from th’ attending Disasters, were look’d upon as Ominous Presages… The One was a large Comet every Evening for a Week… Another was, Flights of Pigeons in breadth nigh a Quarter of the Mid-Hemisphere, and their Length was no visible End… The Third… Swarms of Flies about an Inch long rising out of Spigot Holes in the Earth” (Jameson, p.16).

One afternoon, Mathew encountered a group of Native Americans on his plantation that had arrived to take back three hogs they believed they were owed. Mathew and a small force of armed men perused the natives and killed and wounded a small number of them. The natives soon after retaliated, ambushing Mathew’s plantation, killing a servant and destroying some of his crops. Two men with a small command, Colonel George Mason and Major George Brent, were thereafter sent to attack in retaliation to the native raid, and with thirty men, they killed ten Doeg Indians under a truce of Parley, and fourteen Susquehannahs, a friendly nation, by mistake. These killings took place across the Potomac river in Maryland, and soon became a topic of legal controversy for the two colonies (Jameson, p.106). The Susquehannahs, recently allied with the Picottaway, then began conducting raids on the colonists. The small conflict had spread to nearly every corner of Virginia; not much time passed before the colonists called for action against perceived native aggression that had been steadily increasing in frequency and intensity. (Morgan, p.251)

Berkeley summed a force of nearly one thousand colonists, all armed and trained militia, to siege the Piscottaway fort from which the natives were conducting their operations. Colonel John Washington and Major John Allerton headed the force, lay siege to the fort for “7 weeks during which tyme the English lost 50 men, besides some Horses.” (Jameson, p.106) Five natives were sent out to negotiate peace with the colonists, but they were captured and killed by the English soon after. The siege ended in its seventh week, when the natives made a nighttime escape from the fort, killing ten English guards in the process.

The numbers in this situation and of the conflict from that point onward were fairly self evident and far from fair. During this siege, there were but one hundred native warriors facing a force of over one thousand colonists. Estimates report a total fighting force in the colonies to be about 13,000 men of age to bear arms among the colonists, and about 750 native warriors split among the various tribes of Virginia. The fear of the colonists however was spurred not by shear numbers or by the force of the natives, but by their ability to escape virtually undetected from raids and attacks on colonial plantations. After the siege of the Picottaway fort, the native tribes of Virginia intensified this fear with a war-like series of raids and attacks that would claim the lives of over “300 Christian persons murder’d by the Indians Enemy” (Jameson, p.108). Nathanial Bacon’s own farm was raided by native warriors, and Bacon was scorned by Berkley for the ferocity and scope of his retaliation. The political dimension of the conflict was beginning to boil thick.

The colonists began to cry out for protection and were answered by Berkeley’s second calling for troops, this time numbering over 1,000 men, to directly oppose the hostile native tribes and settle the conflict once and for all. Once on their way, however Berkeley, likely hesitant after his experiences with decades of war, called them back to Jamestown and put a halt on the attack.

The governor proposed and enacted a plan to establish a series of fortifications to be manned by five hundred men along the fall line of the great rivers in Virginia. The colonists were vehemently opposed to this idea. In the eyes of the colonists, the series of forts did nothing to stop raids by native warriors and only established a symbolic territorial claim, which in their eyes had the principle goal of allowing already wealthy aristocratic land owners to expand their fields and increase their crop production. What was worse, the forts were to be fortified by the poorer colonists. Even further, Berkeley outlawed trade with the peaceful native tribal groups that still resided within the colonial territories. This made the less wealthy inhabitants and subsistence farmers furious. In response to the governor’s actions, large masses of unruly peasants began to form, and just south of Jamestown, a small militia army encamped itself in protest (Washburn, pp.30-32).

Unfortunately, this anger was all but unfounded. Berkeley had used such tactics against the Indians in the 1645-1646 wars against the native tribes, and the strategy proved quite effective for safeguarding the colonists from hostiles. The strategy also called for more than just forts. Each fortification had a small mass of troops to protect it, and thus provided a force to attack and surround any native force that tried to attack. Conversely, if a force of natives were to attempt to defeat one of the mobile troop forces, they could be lead or pushed back against the fortification. All of this, however was not successfully communicated to the people of the Virginia colony, and the regular frontiersmen and subsistence farmers could only dread the idea of defense of stationary forts against the native warriors they faced (Washburn, p.32).

Around the time the militia began to encamp, Bacon got word of the goings on. He met with James Crews, Henry Isham, and William Byrd who had all had troubles involving the new wave of native conflicts. As they discussed their grievances, they got word of a group of poorer colonists to the south having the same discussion: the unruly pseudo-army of frontiersmen and subsistence farmers. Bacon and his wealthy companions gathered up a significant amount of wine and liquor and headed off to discuss their grievances with their fellow colonists. (Morgan, p. 255)

This occurrence is somewhat puzzling when Bacon’s character is brought into the picture. Being the flamboyant son of a wealthy English family, Bacon personally despised the lower classes, and loathed men born of a lower station that had established their own wealth. To say that his actions from this point in history forward derived from Bacon’s wish for democracy or for any philanthropy on his part whatever is to completely ignore Bacon’s established character up to that point. It may however explain his tactic to rely upon strong spirits to assist in his communications with the common people (Morgan, pp.254-256)

After a night of drinking, the mob of colonists cheered Bacon on as he promised to lead them in their ventures- so long as they pledged to follow him to their very deaths, and so they did.

Bacon stationed himself in the camp of his new army, and prepared to confront the now hostile native tribes of Virginia. Recognizing and still acknowledging the power of Governor Berkeley, Bacon several times sent correspondence to Jamestown asking Berkeley for a legitimate commission. The governor did not comply with his wishes. Tiring of formalities Bacon took his army and marched southwest to defeat the perceived native menace, which in actuality had been coming primarily from the northeast. The men made contact with the peaceful Occaneechee tribe, who agreed to attack the Susquehannahs for them. The Occaneechees returned with several Susquehannah prisoners, at which point the colonists turned their guns on the both groups of natives and killed Occaneechee and Susquahannah alike. They then launched a campaign around the area of the falls of the Roanoke River and slaughtered any natives, friend or foe, they ran across.

When word of these actions reached Jamestown, Governor Berkeley declared Bacon and his makeshift army rebels and thereby branded the whole lot outlaws by decree. Politics quickly complicated matters for the elderly governor however, for at the outset of conflict Berkeley had called for new elections in order to install a more royalist council with which he could easily work. The conflict rendered the scheme a magnanimous failure. Those in favor of the wholesale destruction of the natives were able to nearly fill the Virginia Assembly, and Bacon, who’s seat had been removed when he was declared an outlaw, was reelected to the assembly within days. When he got wind of his new political success, Bacon decided to return to Jamestown with his lot of men (Morgan, pp.261-262).

When Bacon and his army arrived by boat, they dispatched a small force to meet the governor. When they asked if Bacon would have save passage into Jamestown, they were answered only by a warning shot from the fortresses cannon. Upon hearing the cannon, Bacon attempted a flight upstream but was captured by the governor’s forces, which had already been dispatched in preparation and anticipation of Bacon’s arrival. Bacon’s jig was up.

Amazingly, Berkeley had Bacon brought before him at which point Bacon confessed his wrongdoing and asked for forgiveness. The governor also admitted certain wrongs, restored Bacon to his seat on the council and promised to give him the previously requested official commission. Legislation was passed declaring war on enemy native nations only, and it seemed as though the governor was finally back in touch with the demands of his subjects. Berkeley’s vail of political mercy was quickly and severely lifted. Having placed Bacon willingly under guard, Berkeley rapidly ceased control of the assembly and asserted the old power of the aristocracy. He brought back the former harsh royal taxes and set about to create a stronger military force to win the will of the people. He then sent orders to have Nathanial Bacon dispatched, to rid himself of further opposition and organized unruly masses.

This, however, proved more complicated than Berkeley could ever have thought possible.

Bacon received word from a decidedly more loyal cousin that he was about to be executed and escaped in the night. When Berkeley’s guards arrived to capture Bacon’s head, they instead learned that he had set out to reform his militia and continue his campaign against the natives ( Webb, pp.30-33).

Bacon successfully raised another fighting force, and began looting the lands of the loyalists of the colony to pay back the aristocrats for their attempted play for power and concurrently gain supplies for support of a greater campaign. Governor Berkeley countered by setting out to build a fighting force to oppose Bacon’s newly re-formed militia. Berkeley managed to raise nearly twelve hundred men but when the force learned of its principle object-to fight against Bacon, all but some thirty of the men dispersed. Governor Berkeley took every measure possible to counter the strength of Bacon’s army, going so far as to offer freedom to indentured servants and new lands to the wealthy owners, but to no avail. When Bacon learned that Berkeley had failed to raise an army in opposition and had no standing force, he decided again to return to Jamestown. The governor was forced to flee to the eastern shore, and Bacon marched his army right through the center of the defenseless capitol. A large display of newly captive natives helped Bacon enlarge his force, and the militia army looted the city for supplies and then set it ablaze. On September 19, 1676 Jamestown was pillaged and utterly destroyed.

Early into the governor’s exile, word made it to the colony that an army of trained royalist troops had left England and was on their way to Virginia to quell the rebellion and re-establish the authority of the crown. Bacon marched his army to the mouth of the James to meet the forces head on, but fate conspired against him. Just days before the arrival of the king’s troops on October 26, 1676, Nathanial Bacon died of what was a severe case of dysentery, referred to as the “bloody flux.” The royal troops arrived to find Bacon dead, his forces dispersed, and the governor taking harsh actions to reestablish his authority in the colony.

Governor Berkeley was viewed as being well past his prime and was in large part blamed for failing to quell the rebellion. He was escorted back to England and awaited trial, but was so frail and worn down from the prior years events he died before any action was taken against him. (Washburn, pp.85-87)

In the colonies, the royal authorities set up a council to bring peace and bring reconciliation to the happenings of the past few years and installed Governor Jeffreys, the directly appointed ruler under the king. The looting of loyalist and dissenting colonists against one another continued for nearly four years, but the colony of Virginia was given a stable government and put under direct control of the crown. (Morgan, pp. 267-270)

Bibliography.

Andrews, Charles M. Narratives of the Insurrections, 1675-1690 New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1915.

More News From Virginia 1677 UVA: Tracy W. Mcgregor Library, VA, 1943

Morgan, Edmund S. American Slavery, American Freedom New York:W.W. Norton & Company Inc., 1975.

Standard, Mary Newton. The Story of Bacon’s Rebellion New York: The Neal Publishing Company, 1904.

Washburn, Wilcomb E. The Governor and the Rebel: A History of Bacon’s Rebellion in Virginia NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1957

Webb, Stephen Saunders. 1676: The End of American Independence New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc, 1984.

Wertenbaker, Thomas J. Tourchbearer of the Revolution Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1940

Written Dec. 3 2004. Edited June 2015. HW

LINKS and FURTHER RESOURCES

Thomas Mathew’s account of the rebellion

Excellent NPS Summary and Analysis of the Rebellion

Primary and Secondary Texts from the Rebellion

Wikipedia Article on William Berkeley

ENCYCLOPEDIA VIRGINIA: Bacon’s Rebellion With Many Primary Source scans